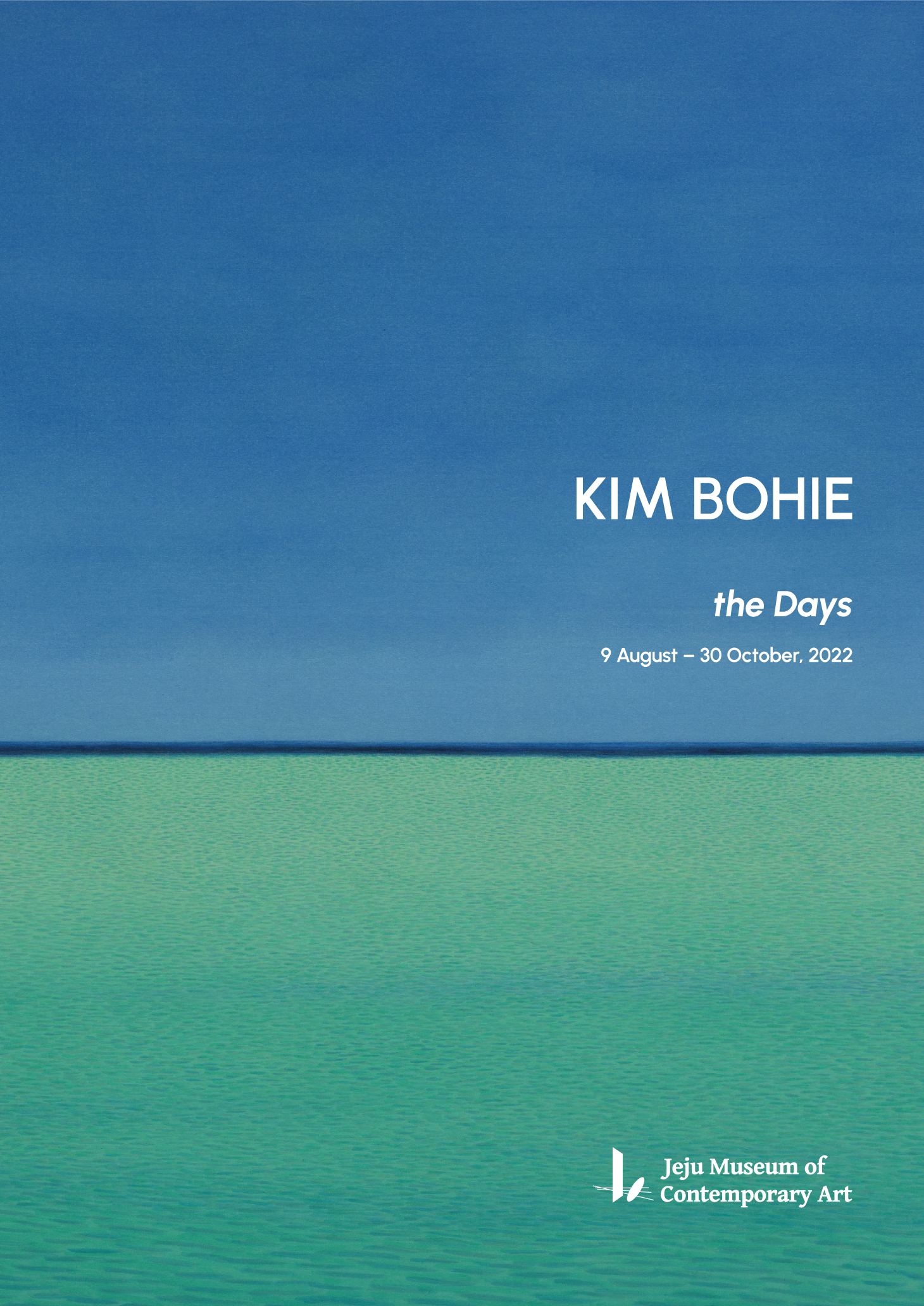

월간미술 2023년 1월호 윤난지 〈그리움을 그리다: 김보희의 생태주의 유토피아〉

그리움을 그리다: 김보희의 생태주의 유토피아

윤 난 지

“ ‘코로나 힐링 된다’ 이 그림 보려고 이렇게 긴 줄이...”

김보희의 개인전(2020, 금호미술관)을 다룬 어느 신문기사 제목이다. 미술관 앞에 긴 줄로 늘어선 사람들, 전시장의 초록 그림과 그 앞에 선 작가 사진이 실린 이 기사에는 “코로나로 인해 몸과 마음이 지친 사람들에게 치유와 회복의 시간을 준 것으로 보인다”는 큐레이터 말이 인용되어 있다. 작가가 제주도로 근거지를 옮긴 2000년대 초부터 집중하여 그린 이 그림들이 생태 위기의식과 맞물려 화제의 중심으로 떠올랐다. 작가의 정원을 그린 것이자 원시 자연에의 열망이 투영된 이 그림들은 질병의 공포를 이겨낼 수 있는 청정 환경의 표상이 된 것이다. 그러나 “이런 반응은 예상하지 못했다”는 작가 말처럼, 이 그림들은 관람자의 반응을 염두에 두고 그린 것도, 팬데믹 시기에 갑자기 그린 것도 아니다. 김보희의 초록 그림은 작가의 오랜 자연 탐구, 그 두터운 역사의 한 발현이다. 그의 이전 작업을 다시 돌아봐야 하는 이유다.

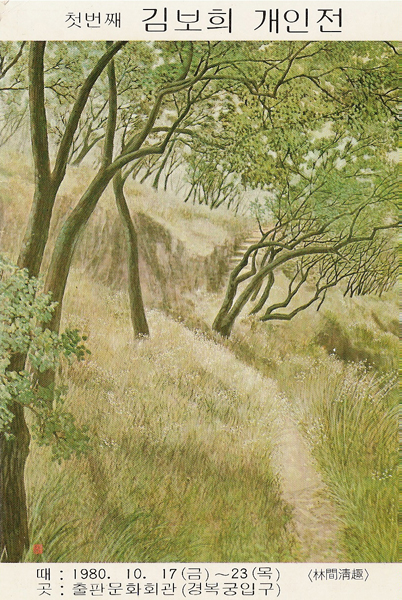

1970년대 후반부터 본격적으로 작업을 시작한 김보희에게 자연은 항상 영감의 원천이 되어 왔다. 동양화 재료로 풍경뿐 아니라 인물, 정물 등 다양한 소재를 그리는 것으로 시작된 그의 작업은 1980년대를 지나면서 점차 풍경으로 수렴되고 1990년대에 들어서면 이른바 김보희의 풍경화 시대가 열리는데, 이는 자연이 김보희 작업의 줄기임을 확인하게 한다. 이 시기의 풍경화는 2000년대의 초록 그림과는 다른, 푸른 색조로 이루어져 있다.

그리움이 그림의 어원이라는 견해가 있는 것처럼, 화가에게 그림을 그리는 것은 그리움을, 그리운 것을 그리는 것이다. 푸른색이 주조를 이루는 김보희의 1990년대 풍경화는 그에게 그리운 것은 자연이라는 사실을 떠올린다. 바다와 하늘 혹은 이 모두를 아우르는 우주의 색인 푸른색은 자연과 그 무한함을, 그에 대한 그리움을 표상하는 색채다. 작은 섬들이 점점이 떠 있는 고향바다 풍경에서 비롯된 김환기의 푸른 점화 혹은 무한한 우주 에너지를 물질 속에 포착하고자 한 이브 클랭의 푸른 모노크롬처럼, 김보희의 푸른 풍경화는 자연과 그 너른 품에 대한 그리움을 그린 것이다.

‘그리운 자연’ 그것이 김보희 그림의 발단이자 평생 과제인데, 초기 풍경화가 그 시작을 알린다. 청평호의 새벽 풍경을 그린 1974년 그림이 좋은 예로, 이는 사실 묘사에 충실한 당시 기법을 드러내면서도 몇 개의 수평선을 따라 나뉜 평면적 구도와 전 화면에 펼쳐진 푸른빛을 통해 이후의 주조색을 예시한다. 그에게 자연은 애초부터 묘사의 대상이자 그리움의 대상이었던 것이다. 채색과 수묵 재료를 함께 사용하는 그는 동양 산수화 전통을 잇고 있는 셈인데, 초기 풍경화에서는 이렇게 실경 산수와 관념 산수의 전통이 교차한다.

1980년대를 지나면서 김보희의 풍경화는 점차 주관적 해석이 두드러지는 방향으로 수렴한다. 새벽 양수리를 그린 〈빛〉(1985)이 그 예로, 이는 제목처럼 풍경을 통괄하는 빛을 그린 것이다. 수묵의 다양한 변조가 빛으로 구현된 이 그림에서 자연은 묘사를 넘어 관조의 대상이 된다. 배면으로부터 어스름하게 배어 나오는 빛이 새벽 여명을 환기하면서 대자연의 신비를 일깨우는 화면은 빛이라는 비물질적인 실체를 통해 자연에 대한 경외심 즉 ‘숭고(the sublime)’를 구현하고자 한 낭만주의 풍경화 전통을 환기하기도 한다.

그림의 주제가 점차 자연 그 자체에서 그에 대한 그리움으로 옮겨오는 과정에서 주요 지표로 주목할 수 있는 것이 선명한 청색, 즉 ‘울트라마린’의 등장이다. 이름처럼, 바다가 상징하는 자연의 무한한 너비와 깊이, 그에 대한 그리움을 담은 색채가 그림 속으로 들어오게 되는 것인데, 1986년 작품 〈을숙도〉가 한 예다. 정밀한 사실주의 기법으로 그린 갈대와 대조되는 푸른색의 넓은 수면은 이후 김보희 그림의 방향을 예시한다. 붓질을 최대한 절제한 짙푸른 수면과 포플러의 검은 색면이 수평, 수직 구조를 이룬 〈미루나무가 있는 강〉(1988) 또한 그의 푸른 풍경화의 단초를 보여준다.

풍경화로만 이루어진 1991년 개인전(현대화랑)은 김보희의 1990년대 작업의 서막을 연 전시다. 단순한 구도와 절제된 색조로 자연의 외형보다는 그것이 환기하는 정서에 방점을 둔 전시작들은 이후 작업의 향방을 예시한다. 예컨대 밤풍경을 그린 〈정(情)〉(1990)은 모노크롬에 가까운 검푸른 색조와 근경의 소나무 뒤에 가까스로 드러나는 먼 하늘의 작은 별들을 통해, 제목처럼, 풍경이 함축한 따뜻한 정서를 표현한 작품이다. 이 전시에는 해변이나 바다 그림들이 다수 포함되었는데, 이는 작가의 마음의 고향인 제주도가 그림으로 구체화되는 과정을 예시한다. 이후 작업에서 푸른색과 검은색이 주조 색채로 떠오르는 것에도 짙푸른 바다와 검은 현무암으로 이루어진 제주도의 독특한 풍광이 주요 변수가 되었다.

영감의 원천이 양수리 등 강에서 바다로 옮겨온 것인데, 이에 따라 울트라마린은 더욱더 전면에 부각된다. 〈효색(曉色)〉(1991), 〈푸른 실내〉(1993), 그리고 이브 클랭의 푸른 모노크롬을 떠올리는 〈무제〉(1995) 등이 그 예다. 작가는 다양한 소재와 형식을 가로지르며 푸른색이 이끄는 감정의 깊이에 몰입해 간 것이다.

이런 변화와 함께 바다 그림들 또한 푸른색과 검은색의 구성으로 단순화되어 갔다. 〈바다〉(1995), 〈제주도〉(1995)가 그 예로, 이런 색채 구성은 산과 강을 그린 이후의 그림들로 이어졌다. 〈산〉(1998)에서처럼, 바다를 대신하는 푸른 강, 바위를 대신하는 검은 산으로 이루어진 화면은 바다 그림과 크게 다르지 않다. 풍경 너머를 보는 작가에게 풍경의 정체는 중요하지 않게 된 것이다.

이렇게 김보희의 1990년대 풍경화는 실경의 구현에서 심상의 반영으로 나아가는 과정을 보여주는데, 검은색 비중이 높아지고 단순한 면 분할이 부각되는 1990년대 후반 그림들이 그 귀결이다. 흑백 그림이 대다수를 차지한 2000년의 개인전은, 〈명상의 풍경〉이라는 제목처럼, 이른바 정신주의(spiritualism)의 궁극적 예를 보여준다. 특히 다양한 표정의 붓질을 통해 드러나는 수묵의 미묘한 변주는 사물의 표피 너머를 관조하는 시선의 추이를 드러낸다. 묵묵히 붓놀림을 반복하는, 마치 도를 닦는 것과 같은 수행 과정을 기록한 그 화면은 관람자 또한 그 과정에 동참하게 한다. 자연의 외형을 보기보다 땅의 기운과 물의 흐름, 살아 있는 것들의 맥박을 감지하게 하는 것이다.

작가의 시선이 점차 사물의 내면을 향함에 따라 화면이 점차 추상화한 것은 당연한 수순이다. 검은색과 푸른색 혹은 노을을 환기하는 분홍빛의 단순한 색면 구성의 2000년대 초 작품들이 그 예다. 자연의 외관을 비추는 거울에서 자연에 대한 주관적 반응을 담은 독자적 실체로 그의 작업이 자리 이동한 것인데, 이는 ‘그림 그 자체로서의 그림’ 즉 ‘회화적 정체성(pictorial identity)’에 대한 작가적 인식에서 온 것이다. 운두를 두껍게 하여 측면으로까지 이어 그린 박스형 작품들과 여러 그림을 하나의 작품으로 구성한 회화적 설치 또한 이런 인식에서 비롯된 것이다. 외형상 미니멀한 이런 작품들은 실은 미니멀리즘과 대극에 있다. 자연에 대한 깊은 감수성을 담아내기 위해 간소한 형태를 취한 김보희의 작품은 모든 일루전(illusion)과 얼루전(allusion)을 차단하기 위해 단순한 물체(object)로 제시된 미니멀리즘과 대비되는 맥시멀리즘이다.

푸른색 주조로 전개된 김보희의 풍경화에 녹색이 주조색으로 떠오르기 시작한 것은 2006년경이다. 이른바 김보희의 녹색 시대가 시작된 것인데, 이는 작가의 제주도 정착(2003)과도 무관하지 않다. 꿈에 그리던 땅에 집을 짓고 정원을 가꾸면서 작가는 자연 속의 삶을 실현하게 되었으며 이런 삶의 변화가 그림의 변화를 가져 왔다. 자연이 먼 꿈이 아닌 눈앞의 현실이 되자 화제(畵題)도 광활한 대자연에서 일상의 소소한 풍경으로, 관념적 고향으로서의 자연에서 살아 숨 쉬는 실체로서의 자연으로 집중된 것이다. 잎사귀와 꽃, 열매 등 식물의 세부를 그리게 된 것도 같은 배경에서다. 밖에서 관조하는 대상에서 안에서 동참하는 환경 즉 각종 나무와 꽃, 동물들로 이루어진 초록의 생태계로 그림의 의미가 옮겨온 것인데, 관람자 또한 그 안에서 싱그러운 숲의 향기와 숨결을 나누는 또 하나의 자연이 된다.

그러나 이러한 녹색 그림은 푸른 그림과 별개의 것이 아니다. 작가는 이전에도 〈풍경〉(1992) 같은 초록 일색 그림도, 나무나 풀, 꽃 그림도 그렸으며, 이른바 녹색 시대에도 푸른 바다 그림을 지속해 온 것이 그 증거다. 녹색과 파란색이 함께 쓰인 그림들(2013)처럼, 김보희의 작업에서 이 두 색은 동전의 양면이다. 푸른색 염원은 초록의 현장으로 구현되고, 초록의 생태계는 푸른 바다와 하늘로 확장되는 것이다.

이처럼, 김보희는 그리움을, 그리운 것을 그려 왔다. 그에게 그리운 것은 모든 인류에게 그리운 것, 즉 자연이다. 밀레니엄이 교차하는, 문명의 질주가 극한에 이른 시기에 문명 이전 세계를 보여주는 그의 그림은 우리 모두에게 그리운 것은 자연이라는 사실을 일깨운다. 관념 산수와 낭만주의 풍경화, 프리미티비즘과 모노크롬 추상 등 동서고금을 넘나드는 그의 어법은 이런 사실을 더욱 넓고 깊게 깨닫게 한다.

김보희 그림의 힘은 무엇보다 자연을 대하는 시선의 위치에 있다. 낮은 위치에서 자연에 다가가는 시선을 담은 그의 그림은 자연과 함께 있음을 체감하게 한다. 그것은 자연을 한눈에 담고자 하는 높고 먼 시선, 이에 근거한 주류 풍경화 전통을 벗어난 지점을 가리킨다. 그는 풍경이라는 전통 주제를 동시대적 요구에 부응하는 시각으로 재해석한 셈이다.

태초의 자연을 그린 것이자 미래적 비전을 담은 김보희의 화면은 특정한 시간과 공간을 넘어선 이상향 즉 ‘생태주의 유토피아’의 도상이다. 그것은, 〈Towards〉라는 근작 제목처럼, 인류가 ‘지향해야 할’ 진정한 파라다이스, 모든 생명체가 평화롭게 공존하는 자연환경을 촉구한다. 예술의 사회, 윤리적 차원을 떠올리는 지점이다.

모든 유토피아 도상처럼 김보희가 보여주는 이상향은 ‘좋은(eu) 곳(topia)’이자 ‘없는(ou) 곳(topia)’ 혹은 없기 때문에 좋은 곳이다. 김보희의 그림 또한 유토피아의 역설에서 자유로울 수 없는데, 사실 모든 그림은 이러한 역설에서 나온 것이다. 없으니까 그리운 것이다. 그리고 그리우니까 그리는 것이다. 김보희도 그렇다.

Picturing of longing: Ecological Utopia by Bohie Kim

Nanji Yun

“’What a healing from COVID-19 pandemic’, lining up stretches to see a painting…”

It is the title of a newspaper article introducing Bohie Kim’s solo exhibition (2020, Kumho Museum of Art). The article – with the attached illustrations of visitors far lining up to the museum entrance, and the artist standing before her green painting – quotes the curator’s remark, “it seems like the ones who are exhausted by the pandemic inside and out are provided with a moment of healing as well as recovering.” These works, which the artist has focused on since the early 2000s when she relocated to Jeju Island, have emerged as the highlighted issue in conjunction with the prevailing consciousness of the ecological crisis. The paintings describing the artist’s own garden and reflection of yearning for the primal nature have become a representation of purifying environment that could overwhelm the fear of disease. As implicated in the artist’s comment, “I have never expected such a response,”[1] creating these works has never been concerned with such an expectation from the viewers or rooted by the sudden urge during the pandemic. Bohie Kim’s green paintings are a manifestation of the artist's long exploration of nature and its deeply layered history. It demands her previous works to be brought into the context.

Nature has always been a source of inspiration for Bohie Kim, who began working as a devoted practitioner in the late 1970s. Her work, which departed by painting various subject matters not limited to landscapes but including figures and stills using materials in oriental painting, converges into landscapes during the 1980s; the 1990s introduces so-called the landscape era of Bohie Kim, confirming that it is the nature that streams within Bohie Kim’s practice. The landscapes in this period consist of the blue hues, altering from the green work in the 2000s.

As there is an understanding that the Korean word for longing is the etymology of picturing, painting for a painter is to picture longing, what she longs for. Bohie Kim’s landscape paintings in the 1990s, which are led by blue, imply that it is nature she longs for. Blue, the color of the universe that encompasses the sea and the sky, or both, is a color that represents nature, its infinity, and longing for it. Like Whanki Kim’s blue pointillistic painting from his hometown seascape, where small islands float in dots here and there, or Yves Klein’s blue monochrome to capture the infinite cosmic energy in matter, Bohie Kim’s blue landscapes depict longing for nature and being in its open arms.

‘Nature to long for’ is the outset and lifelong object of Bohie Kim’s painting that the early landscapes mark its beginning. A suitable example is the 1974 painting of the early morning scenery of Cheongpyeong Lake, which reveals the techniques of the time faithful to realistic description yet foreshadows the subsequent central color; it is implicated in the flat composition distributed along several horizontal lines and in the blue illuminating over the entire picture. For her, nature had been the object of description and the object of longing from the beginning. Employing application both of colors and ink-and-wash materials, she seems to follow the trajectory within the tradition of oriental landscape painting; and her early landscapes traverse the traditions of representational landscape and conceptual landscape as such.

Passing the 1980s, Bohie Kim’s landscapes gradually converge to a point that highlights her subjective interpretation of them. Light (1985), which depicts Yangsu-ri in the early morning, is an example of the light that gently grasps the entire landscape as reflected in the title. In this painting, where variations of ink-and-wash are embodied in light, nature becomes an object of contemplation beyond its description. The pictorial surface - in which the light is smearing from its rear - evokes the aura of the dawn to reveal the mysterious essence of Mother Nature; as well as the romantic landscape tradition of manifesting the awe of nature, ‘the sublime’, through the immaterial reality of light.

In the gradual progress of Bohie Kim’s painterly objective shifting from nature itself to longing for it, the emergence of clear blue, the ‘ultramarine’, can be remarked as a significant indicator for the transition. As the name of the color suggests, the infinite span and depth of nature symbolized in the sea, longing for which is contained in a color brought into the picture; and the 1986 work Eulsuk Island makes an example of it. The wide blue water surface, contrasted with the reed touched by precise realism, suggests the path leading to Bohie Kim’s forthcoming work. Poplar Tree At River (1988), in which the deep blue water surface using utmost restrained brushstrokes comprises a horizontal and vertical composition with the black color planes of the poplar tree, also indicates the beginning of her blue landscape work.

Bohie Kim’s solo exhibition in 1991 (Hyundai Hwarang), which consists only of landscape works, has been the prelude to her practice in the 1990s. The exhibited works hint at their later terms by highlighting the emotional arousal over the general appearance of nature by using simple composition in contained color. Sympathy (1990), a night landscape, demonstrates the warm sentiments implied by the landscape of the almost monochromatic dark blue shades, and small stars shy in the distant sky cast above the up-close pine tree. The exhibition included several beach and sea paintings, signifying that the artist’s embracement of Jeju Island as where her heart belongs progressively manifested in painting. In the later work, the unique scenery of Jeju Island, which consists of a deep blue sea and black basalt, became variable factors that influenced the leading tones of blue and black colors.

The source of her inspiration has shifted from Yangsu-ri and other rivers to the sea, by which Ultramarine becomes ever more prominent. Examples include Dawn (1991), Blue (1993), and Untitled (1995), which evokes Yves Klein’s blue monochromes. The artist was immersed in the depth of emotions led by blue, crossing various materials and forms.

Along with these changes, the sea paintings have progressed to simplified blue and black compositions. Sea (1995) and Jeju Island (1995) are examples, and this color scheme led to the works following the ones of mountains and rivers. As in Mountain (1998), the river replacing the sea, and the black mountains replacing the rocks make up a picture that is not much deviating from the sea paintings. The identification of the landscape has become insignificant to the artist whose eyes reach beyond that scenery.

This progress illustrates the trajectory of Bohie Kim’s landscape paintings in the 1990s moving from the realization of realistic scenery to the reflection of the inner image, which resulted the works in the late 1990s with emphasized blacks and simplified planar division. As suggested in the title of her solo exhibition in 2000, Landscape of Meditation, which was mostly comprised of black and white works, ultimately demonstrating what is called ‘spiritualism.’ In particular, the subtle variation of ink-and-wash revealed within the diverse expressions of brushstroke illuminates the gaze that reaches beyond the epidermis of objects. The picture of silent, repetitive brushstrokes, in which the marks of meditative practice – such as in Tao – is embedded, invites its viewer to join the process. It carries the viewer over the appearance of nature and let one sense the energy of the ground, the flow of water, and the pulse of living things.

It is only natural that her pictures progressed to abstraction, corresponding to the artist’s gaze turning toward the inner side of objects. Examples include works from the early 2000s with simple planar color compositions of black and blue, or pink that evokes the sunset. Her work shifted from reflecting the appearance of nature to standing as an independent entity that contains a subjective response to nature; which derives from the artist’s perception of ‘picture as a sufficient being as itself’: the ‘pictorial identity’. The box-shaped works with the thickened clouds extending to their edges and the painting installation consisting of several pictures also stem from such a perception. These works appear minimal yet in fact are contrary to minimalism. Bohie Kim’s work, which took a simplified form to capture in-depth sensitivity to nature, is presented as a simple object to eschew both illusion and allusion entirely, contrasting minimalism with maximalism.

It was around 2006 when green began to emerge as a central color in Bohie Kim’s landscapes evolved under blue. What is known as the green era of Bohie Kim has begun, relevance of which is not apart from her settlement in Jeju Island(2003). By building a house and gardening on the land she had dreamed of, the artist realized the life within nature, and this transition in life brought about a change in her painting. As nature became a tangible reality before the artist’s eyes rather than a distant dream, her painterly focus shifted from the vast Mother Nature to the images of small life, and from the nature as an ideal origin to the nature as what breathes into reality. It is under the same context that the details of plants such as leaves, flowers and fruits were described. The meaning of painting has shifted from an external object of contemplation to an environment to participated within, which is the green ecosystem of various trees, flowers, and animals; the viewer also becomes another part of that nature to share the scent and breath of the refreshing forest.

However, these green paintings are not distinctive from the blue paintings. Evidently in the past, the artist has painted green monochrome works such as Landscape (1992) as well as the pictures of trees, grasses, and flowers, and continued to paint blue sea paintings even during so-called the green era. Like the paintings with green and blue combined (2013), these two colors are the two sides of the same coin in Bohie Kim’s practice. The blue yearning is manifested in the green sites, and the green ecosystem expands into the blue sea and the sky.

As such, Bohie Kim has been picturing longing, what she longs for. To her, what she longs for is what humans long for, which is nature. Her paintings of the nature prior to civilization reminds us of the fact that what we all are missing is nature - at a time when the millennium intersects, and the speeding of civilization reaches its extremity. Her painterly principles, which transgresses the ages of East and West, such as conceptual oriental landscapes and romantic western landscapes, primitivism and monochrome abstraction, bring us together into a deeper and broader understanding of realization.

The power of Bohie Kim’s painting, above all, lies in the position of her gaze toward nature. Her painting, which captures that gaze of approaching nature from below, place the viewer in togetherness with nature. It refers to a point diverging from the tradition of mainstream landscape painting, which derives from a high and distant point of view to capture nature at a single glance. She reinterpreted the traditional subjecthood of landscape seen through a perspective that corresponds with contemporary demands.

Bohie Kim’s picture, which illustrates the primordial nature and contains a futuristic vision, is an icon of utopia, that is to say, ‘ecological utopia’ beyond any given time and space. As suggested in the title of her recent series Towards, it calls for a true paradise, which all humans ‘ought to aim for’, and a natural environment within which all living things are in peaceful coexistence. It is a point of reminding the social and ethical dimensions of art.

As in every icon of utopia, the one Bohie Kim presents is a ‘good(eu) place(topia)’ at the same time ‘no(ou) place(topia)’, or a place deemed good because it does not exist. Bohie Kim’s work cannot be free from the paradox of utopia, yet all pictures derive from such a paradox. Longing is towards what is not there. And we picture it as we long for it, then so does Bohie Kim.